March 30, 2011 -- Anderson County, Kentucky

The Boulevard Distilling

Company |

BOURBON, at least old-line, traditional, Kentucky bourbon,

owes much of its appeal to its sense of heritage. When one picks up and sips a

fine example of bourbon, certainly a large part of the pleasure is the feeling

that you are sharing an experience with people from a time which is long past,

but always revered. Dozens of old familiar brands continue to be sold and

enjoyed, despite the fact that most are produced by only a handful of companies,

and most of those bear no relationship to the original whiskies other than the

legal right to use their names. Of course, it’s good whiskey; none of those

distillers puts out junk, not even for their lowest-priced product. But you

can’t deny that all that history and tradition we read on the label goes a long

way toward our desire to drink it.  Not all Scotch is

that way; nor is it (always) true of tequila, or rum. Or certainly for gin or

vodka. But a drink of bourbon is, for most of the folks whom their merchants

target, a visit with our grandfather, or maybe a past President, or at least a

plantation owner with thoroughbred horses and fields of fine tobacco (for cigars

and pipes, of course).

Not all Scotch is

that way; nor is it (always) true of tequila, or rum. Or certainly for gin or

vodka. But a drink of bourbon is, for most of the folks whom their merchants

target, a visit with our grandfather, or maybe a past President, or at least a

plantation owner with thoroughbred horses and fields of fine tobacco (for cigars

and pipes, of course).

Or maybe just a few friends who like to go hunting together when the leaves are getting all gold and rust. The morning air at that time of year carries a chill that feels so welcome after weeks of sweltering summer heat, and dogs flush out quails and pheasants, and wild turkeys.

Especially wild turkeys.

Every brand of American whiskey has something unique and

valuable about it.

The bourbon made at this distillery has it on all counts.

For starters, let’s look at it’s name. We say “it’s” name because they only make one kind of bourbon whiskey here, and that’s Wild Turkey. They’ll bottle it at 80 proof if you prefer a less-imposing whiskey flavor, or at 101 proof if you’d like the extra heat (and which is the version they’re most famous for). Or you can get it the way the distiller himself prefers, at around 108 proof, which is how it comes out the barrel, without any dilution at all. It’s all Wild Turkey.

It wasn’t always Wild Turkey, though, and here’s where the story of this distillery, and this brand, and this bourbon begins to get really interesting. Because, you see, they all came to the party from different places…

The distillery came first.

It, or at least the first distillery at this site, was

built in the 1850s and operated under the name “Old Moore”.

In 1888 the

distillery was purchased by Thomas B. Ripy, whose family owned and operated several

in the area. In fact, between the Ripys, the Dowlings, the Waterfills, the

Fraziers, the Browns, and the McBrayers, Anderson County probably produced more

bourbon whiskey in the last half of the 19th century than anywhere

else except Louisville (and most of those folks were involved in several

distilleries in Louisville, as well).

In 1888 the

distillery was purchased by Thomas B. Ripy, whose family owned and operated several

in the area. In fact, between the Ripys, the Dowlings, the Waterfills, the

Fraziers, the Browns, and the McBrayers, Anderson County probably produced more

bourbon whiskey in the last half of the 19th century than anywhere

else except Louisville (and most of those folks were involved in several

distilleries in Louisville, as well).

Lots more than ever came out of Bourbon County, by the way. So how come they call this kind of American whiskey “Bourbon” instead of “Anderson”? Oh well, that'll be another story.

Anyway, in 1891 the buildings were torn down and the place was

rebuilt as the Old Hickory Springs distillery.

Their product was called simply “J. P. Ripy”, and in 1894 they partnered with Ike Bernheim (I.W. Harper) and the name was

registered in Louisville.

In those days there was a distinction between distilleries, which made whiskey and wholesalers, who used that whiskey to make the product they sold with their name on it. In fact, most of the popular brands were put together by merchants (such as Bernheim or Weller) who purchased whiskey from various distillers (like Ripy, or Stitzel, or perhaps even both) and then mixed them together to form their finished product. In the Ripys’ case, they owned several distilleries for their wholesale customers to choose from.

Thomas Ripy died in 1902 and the Ripy distilleries were

assimilated into the Kentucky Distilleries and Warehouse Company (the notorious

Whiskey Trust). Prohibition put an end to the Trust, as well as to just

about all the distilleries, including those of the Ripys. And although the “Ripy

Bros.” brand was resurrected (by the Schenley company) after the end of

Prohibition, that was only the brand, not the distillery in Tyrone.

The Ripy’s,

who still owned the property, restored the distillery to operational condition

and again began making fine bourbon under contract for other companies. We haven’t been able to confirm whether

they were a source (perhaps even the only source) for the whiskey bottled by

Schenley as Old Ripy Bros., but we feel it was likely.

The Ripy’s,

who still owned the property, restored the distillery to operational condition

and again began making fine bourbon under contract for other companies. We haven’t been able to confirm whether

they were a source (perhaps even the only source) for the whiskey bottled by

Schenley as Old Ripy Bros., but we feel it was likely.

And Schenley would not have been the only ones, either. The Ripys were also making the whiskey that ended up as J.T.S. Brown, Old Joe, Dowling, Belle of Anderson, and several other brands. And not just from the distillery we are visiting today, either; they operated several – including another that still exists, the Old Prentice distillery… now known as Four Roses. And whiskey wholesalers (including Schenley, Bernheim, and others) bought Ripy whiskey to use in their own products.

One of those wholesalers was a New York City grocery firm by the name of Austin Nichols & Company that had also been around since the late 1800s. Think of them as being somewhat equivalent to Whole Foods today. Anyway, to whatever extent they may have handled wines and spirits, that part of the business ended with the Volstead Act in 1920, but was again available after Repeal. Not only available, but downright lucrative. So much so that, by 1938 Austin Nichols & Co. had closed down most of its other product lines and concentrated its attention only on fine wines and liquors.

Kentucky Bourbon was one of those liquors.

They called it Austin Nichols Bourbon, and they used whiskey from various contractors, each of whom bottled it with the Austin Nichols label.

Among those distillers were the Ripys.

According to legend, in 1940 the president of Austin Nichols, Thomas McCarthy, got the idea to further designate their bourbon whiskey as “Wild Turkey”, in order to capitalize on its popularity among his fellow turkey hunters – perhaps out on Long Island (the official story claims South Carolina, but that may have been substituted because it seems more “Southern”-sounding; the Austin Nichols company itself was located in Brooklyn).

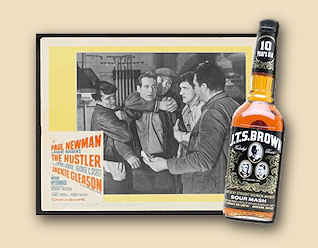

The actual whiskey in a bottle of Wild Turkey was not specific to any one distillery, nor did Austin Nichols have their whiskey custom-made to a proprietary formula; they just bought whatever tasted good. Over the years, however, they came to be more and more pleased with the flavor and quality (and probably the price) of the bourbon produced at Tyrone. By that time the distillery was owned by Robert Gould, who was producing J.T.S. Brown bourbon there. Next time you have a chance to see the movie “The Hustler”, it might be interesting to think about the fact that the “cheap rot-gut whiskey” that Fast Eddie (Paul Newman) specifies in his epic playoff with Minnesota Fats is (or at least was when the movie was filmed) the very same whiskey that filled the bottles of Wild Turkey (probably America’s premier bourbon at that time).

Why do we know It was the same whiskey? Because that’s the only bourbon they made at that distillery – no matter whose label was on the bottle. And in the early ‘60s when “The Hustler” was filmed, “they” meant distiller Jimmy Russell.

And that brings us to the bourbon part of our story.

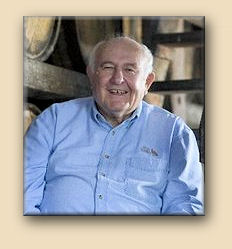

Jimmy Russell (a big guy; he was known as “Russell the Muscle” in

those much younger days) began working for the Ripys in 1954. Today (2011) he

has been there for nearly sixty years. Can you BELIEVE that?? And it won’t end

when he finally decides he’d rather be fly-fishing, either, because his son Eddie

is pretty much running the show now and will likely be doing so for the next few

decades. Ed isn’t exactly a teenager just breaking into the biz, either – he’s

been working at the distillery for over thirty years already!

Jimmy Russell (a big guy; he was known as “Russell the Muscle” in

those much younger days) began working for the Ripys in 1954. Today (2011) he

has been there for nearly sixty years. Can you BELIEVE that?? And it won’t end

when he finally decides he’d rather be fly-fishing, either, because his son Eddie

is pretty much running the show now and will likely be doing so for the next few

decades. Ed isn’t exactly a teenager just breaking into the biz, either – he’s

been working at the distillery for over thirty years already!

Jimmy Russell makes bourbon whiskey.

He only makes it one way. He’ll be the first to tell you, and proudly at that, that his way isn’t the only way; it may not even be the best way (that’s for you to decide); but it’s the way he makes bourbon whiskey.

Jimmy will tell you that he worked for the Ripys, and he probably did – as far as the operations at Tyrone went. But the distillery itself was owned by Robert and Alvin Gould of Ohio since 1949. We suspect that, whoever might have legally owned the place, it was Jimmy Russell who continued to make whiskey there. And that concept has held true throughout the distillery’s life, right up to today.

By the end of the ‘60s, Austin

Nichols understood that the little distillery in Tyrone (now known as the

Boulevard Distillery) was making exactly the bourbon they wanted, and by then

they weren’t really even buying from anyone else.

That

was a very bad time for whiskey distilling, and independent distilleries were

shutting down one after the other. Someone at Austin Nichols had the very

insightful idea that they'd better lock up their vendor system or risk being put

out of business when all their suppliers failed.

That

was a very bad time for whiskey distilling, and independent distilleries were

shutting down one after the other. Someone at Austin Nichols had the very

insightful idea that they'd better lock up their vendor system or risk being put

out of business when all their suppliers failed.

So, in 1971 they bought the

Boulevard distillery from the Goulds and it became their sole provider of

Kentucky bourbon. And eventually their rye whiskey, too, after their

Pennsylvania sources closed up (see, they were right, weren't they?). It is

still officially the Boulevard Distillery, but the sign says Wild Turkey, and

that’s what everyone knows it as. It is located in Tyrone, Kentucky, on Wild

Turkey Hill.

And don’ you forget it.

In 1980, Austin Nichols (which, by now, was pretty much

Wild Turkey and nothing else) was purchased by the French beverage giant Pernod-Ricard.

The brand, and the distillery.

And Jimmy Russell.

And Wild Turkey continued to be made exactly the same way

it always was.

In the next quarter-century, major changes swept through the American spirits industry (indeed, the whole world’s spirits industry). Changes that were beneficial to some and disastrous to others. Major brands changed hands, and the whiskey actually in the bottle changed dramatically.

Not so much at Wild Turkey, though. Jimmy Russell continued to make whiskey the way Jimmy Russell makes whiskey. It came off the still at a lower proof (meaning with more flavor elements) than the others, which it still does. It went into the barrels the same way, which it still does. And Wild Turkey continued to be bottled at 101 proof, just like it always was. And still is.

Have there been NO changes?

Well, of course there have been; did you want the company to go out of business

like so many others? Of course not.

But it hasn't really changed much.

Okay, Wild Turkey isn’t 8 years old anymore, there is younger whiskey in the

bottle now.

That may be less a result of cost-cutting than of making sure they don’t run out

of product. Eddie Russell is in charge of "warehousing and aging" (i.e., his job

is that of the wholesaler, who was once considered to be the person whose

product a particular brand of bourbon was) , and his decisions have resulted in

a bourbon with all the richness of the older version. One reason for making that

decision might have been to free up some product for the 10-, 12-, and even

15-year old expressions that Wild Turkey now offers.

The taste of bourbon whiskey has changed over the years. That should not be surprising; the taste of everything – even Tootsie Rolls – has changed. But of all the bourbon whiskies commonly available today, Wild Turkey remains the closest to the way it was fifty years ago. And in the world of bourbon values, that is probably the most complementary thing a person could possibly say. At least, we mean it to be.

And last year Pernod-Ricard sold their Austin-Nichols interests to the Campari group, an Italian beverage company.

So, what about the distillery itself; after all, isn’t that

what we’re visiting?

Okay, are you familiar with term “no

frills”?

Well, that’s the best description for Wild Turkey.

The bourbon ----- the distiller ----- and the distillery.

First, let's get there. For the visitor, there are two ways:

You can drive east from Lawrenceburg on U.S. Highway 62, and veer to the right at the sign.

Or you can drive west from Versailles (that’s Vuhr-Sayles,

y’all), again on US 62, which is the more spectacular way. Why? Because you have

to cross the Kentucky River over the scariest d@#m bridge you’ve ever seen,

that’s why. Well, all right, the “S” curved bridge you’ll be driving on is not

the scary one; the scary one is the railroad bridge that runs alongside of you.

But just seeing that bridge is enough to be worth taking that route.

The

railroad bridge, known as Young’s High Bridge, was built in 1889, and it's one

of the oldest and tallest railroad bridges still standing today. It’s a cantilever bridge,

meaning it juts out over open space from its supports, and the railroad track is

on top of the bridge, above the beams and braces. It looks as if it’s upside

down. Photos of trains on the bridge, lined up to receive whiskey from the

distillery, look like they’re about to fall off. None ever did, and that won’t happen while we’re

here today, either; the last train crossed Young's High Bridge in November 1985.

The

railroad bridge, known as Young’s High Bridge, was built in 1889, and it's one

of the oldest and tallest railroad bridges still standing today. It’s a cantilever bridge,

meaning it juts out over open space from its supports, and the railroad track is

on top of the bridge, above the beams and braces. It looks as if it’s upside

down. Photos of trains on the bridge, lined up to receive whiskey from the

distillery, look like they’re about to fall off. None ever did, and that won’t happen while we’re

here today, either; the last train crossed Young's High Bridge in November 1985.

It also affords a sneak-preview of a skyline unknown before 2011... the new Wild Turkey distillery.

Whichever way you choose to get here, assuming you’re not squashed by one of the quarry trucks that also call Tyrone Road theirs, you will arrive at the Boulevard Distillery (yes, it’s still called that) visitors’ parking lot.

Until this year, if you visited Wild Turkey

after exploring Woodford Reserve’s “restored

monument”-like site, or Maker’s Mark’s “Disney-quaint” site, you were likely to

experience a bit

of a shock. Wild Turkey was, and still is, a place where they concentrate their

attention on making whiskey, not pretty photo scenes. That's not to say they

don't appreciate guests -- in fact they love guests -- but the distillery

they've shown their guests has been pretty no-frills.

Some might say even a bit

worn-out looking.

In fact, some have said that.

But no more. This year (2011) there is something new... Everything.

The entire distillery operation has been

expanded, to the tune of about double it's former capacity. The way this was

done was to build a completely new distillery on the hill above the original

one. The site is where once stood a 7-story warehouse full of about 17,000

barrels of Wild Turkey bourbon that caught fire (the warehouse; not the barrels) eleven years ago

(the barrels just rolled down the hill and into the Kentucky river... which

presented some challenges in their own right).

The original distillery had some old cypress fermenting tanks and had already begun replacing them with stainless steel ones as they wore out. By the late '90s they were all stainless steel, about 15,000 gallons capacity each. The new distillery has 23 gleaming stainless steel fermenting tanks, each with a capacity of over 30,000 gallons of mash.

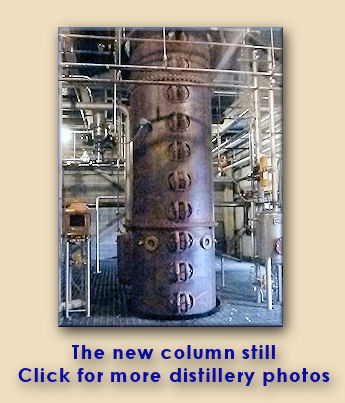

The column still itself is also new, but it is not shiny stainless steel (nor is the pot-still doubler) . Unlike vodka or gin, bourbon needs interaction with copper in order to taste right. Some distilleries use stainless steel column stills, but put copper baffles inside to provide that contact; some use stills made entirely of copper. Wild Turkey's new still, just like it's old one, is all copper, and after only a brief time of use it has already developed a patina that makes it look the same as a fifty-year old still. Hopefully the whiskey from it will taste the same -- of course, we won't know for several years. The bourbon going into these barrels won't be bottled until at least 2016, and probably later than that.

There's another thing different, beginning now: visitors can now see the whole process in action. That wasn't true before. Oh sure, the tour guides could show you selected parts of the process, but not while they were in actual use. Not so with the new facility. Everything's open and observable and the tour is much more comprehensive. Our guide, Reva, began working here a little over a year ago, back when the old distillery tours were often limited to just the bottling line and the warehouse. She is very excited about taking visitors around the new installation and being able to demonstrate how her whiskey is made.

Did we say "her" whiskey"? Yes, we sure did. Reva considers Wild Turkey bourbon to be "her" whiskey just as much as it is Jimmy or Eddie Russel's. So does everyone here. That's just the way it is.

The warehouses & bottling

plant are still in use, but the old distillery itself is now closed down

Reva proudly shows off the brand new distillery at the top of the hill

When Wild Turkey's distilling operations closed down for the summer last year, Reva had the honor of leading the last public tour through the old distillery, and now she's bringing the first folks through the new facility. She says she knows that some guests will be disappointed in the new distillery, simply because it's new, and shiny, and hasn't had the decades to develop the charmingly grungy look that the old equipment had. As we said at the beginning of this tale, heritage and tradition play an important role in our experience of America's Spirit. But Reva is quick to remind us that "...you know you always have to start something new in order for it to become history".

Oh, and by the way, DON'T VISIT HERE IN THE

SUMMER!

Don't visit ANY distillery in the summer.

The first part of whiskey is purely

agricultural, and seasons count.

Yeast doesn't like summer heat.

That means that distilleries don't mash grain between early July and late

August.

You'll miss all the good parts if you visit during summer.

![]()