| American

Whiskey

September 14, 2000 Heaven Hill... The New Kid In Town?

|

|||

NEARLY TWENTY-FIVE years ago, on a visit to Kentucky, John was served Hot Brown in a restaurant. He was told that the hot turkey sandwich, served open-faced on toast, smothered with Mornay sauce, topped with tomato and bacon slices, and broiled was a Kentucky tradition.

Now that we live just minutes from the Bluegrass State, we know a little

more about this wonderful dish.

It was also an instant success, and was carried over to the hotel's lunchtime menu where it soon became a midday favorite. Before long, Hot Brown sandwiches were being served all over Louisville and the rest of Kentucky. It's so popular today that even Governor Paul Patton's wife Judi offers a recipe on the internet (http://www.state.ky.us/agencies/gov/hotbrown.htm).

THE CAMBERLEY BROWN, as the hotel is known today, still serves Hot

Brown the same way it was created nearly eighty years ago, and this afternoon,

it is serving it to us. As we sit in the hotel’s bright and cheery luncheon

restaurant, called J.

Graham’s Café, we are presented with the finest Kentucky

Hot Brown either of us has ever eaten.

Leaving the Camberley Brown Hotel, we have only a short drive of a few blocks to the BERNHEIM DISTILLERY, essentially next door to the Brown-Forman world headquarters and corporate offices we’d toured two years ago.

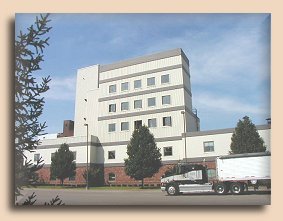

When it was built by United Distillers in 1992, the Bernheim distillery was

the cutting edge of bourbon-making technology. It still is. Sitting in the

shadow of the old brick warehouses, Bernheim is the most modern bourbon

distillery in existence, as the somewhat newer Labrot & Graham facility

was intentionally made to be as traditional as possible and uses technology

from the 19th century wherever it can.

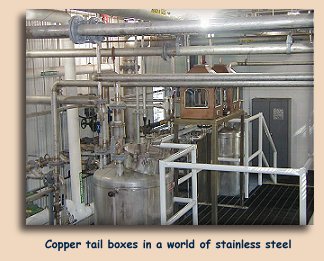

When United Distillers, a division of Guinness, purchased those brands they

bought everything, the labels, the old stock, and the distilleries themselves.

For a number of reasons, certainly not the least of which being that it was a foreign-owned company whose operations were directed from overseas by managers who may have considered bourbon a competitor to their primary interests, United’s presence was not particularly welcomed by the established distillers. Add to that the fact that their decision to close down a beloved landmark, the Stitzel-Weller distillery, came almost immediately after they took over and it’s easy to understand why United Distillers was more or less universally scorned. Bernheim, shiny and new, filled with modern stainless steel machinery and computerized production equipment, is the very antithesis of everything Stitzel-Weller had once stood for. That plant, where whiskey was distilled surrounded by full copper and wood and valves operated by human beings, proudly displayed, near the entrance to its offices, a sign stating, "No Chemists Allowed!". So the change to Bernheim was seen, symbolically, more as the loss of a proud old (and probably mythical) tradition than merely a transfer of manufacturing location.

None of which matters today. For all the wailing and gnashing of teeth over

what United would do to the brands it had taken over, they were only there

for about seven years before merging with another British mega-company, IDV,

to form Diageo. The new conglomerate has little interest in maintaining bourbon

brands at all nor in operating a bourbon distillery in far-off Kentucky,

USA.

Today we aren’t planning on getting a full tour of the Bernheim plant.

Unlike their Bardstown location, famous for its distillery tour which includes

historic parts of the the town as well, no public tours of Bernheim are offered

yet. United Distillers also didn’t give public access, so most people

have never seen the inside of the distillery. We are hoping to be able to

find some spots outside the fences where we can take some photos, but as

we drive up to the front gate we see a festive, open-sided tent with tables

and chairs. They’re all empty; it looks as though a party has recently

ended. The gate is open, so we drive in and pull up to the security office

to see if they’ll let us shoot some pictures from inside the grounds.

Instead, the guard tells us that they have just finished the formal dedication

of the new plant and he asks us to wait while he calls one of the public

relations folks over. She, in turn, welcomes us warmly even though she knows

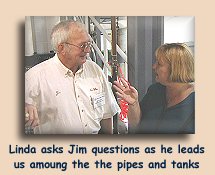

we aren’t part of the press corps and calls Jim Land, the production

manager. He then graciously offers to take us on a private tour of the

whole

facility.

At a display of Heaven Hill's product line, Jim points out the Old Fitzgerald

bottlings that Heaven Hill has acquired in the purchase. "Ol' Fitz" has been

a well-loved bourbon for decades, and the folks at Heaven Hill are proud

to be making it. The only changes they expect to make, says Jim, are to restore

some of the "human touches" that were lost when production was first moved

here from Stitzel-Weller. Jim next takes us to a large wall-mounted

display showing a graphic chart of how the distillery works. We go over some

of the ways in which the Bernheim distillery is different from what they

were used to in Bardstown. Then he shows us one of the most challenging

differences. The old Heaven Hill distillery was pretty much run by people

flipping switches and turning valves. The Bernheim plant is entirely

computerized. Fortunately, most of the operators applied to be hired on by

the new owners, and the previous Heaven Hill staff were able to be trained

to use the new technology.

As he takes us through the distillery, Jim points out how and why certain

features were built the way they were, and in several places where changes

have been made to improve the product quality. The Bernheim plant uses enclosed

fermenting tanks. In all the distillery tours we've taken before, we've had

ample opportunity to inhale the wonderful fragrance that surrounds open

fermenters. But we'd never had our noses inside a closed fermenter

before. Now that may seem like a small detail, and indeed it goes entirely

unnoticed.

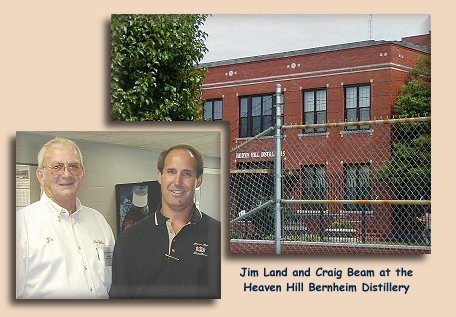

Jim makes sure we spend as long at we like at every portion of the tour,

and that our questions (sometimes difficult ones) are all answered. His

presentation is outstanding and, as we reach the end, we have a chance

to meet and talk to Craig Beam, Master Distiller Heir Apparent. Craig also

talks with us as if we were the most important people to ever visit Heaven

Hill. The degree of hospitality is extraordinary, especially since we had

simply dropped in, unannounced, at the end of what had already been a busy

and disruptive day for the whole staff. I don't think we could have been

more impressed.

Be sure to come with us and see the rest of the

Heaven Hill facilities in Bardstown, including the warehouses where all Heaven

Hill whiskey is aged, the bottling line, and the remains of the original

distillery (with news photos of the horrendous 1996 fire that destroyed

it).

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright © 2000 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

First

of all, we know that it really is a regional tradition. Outside of Kentucky

almost no one has ever heard of Hot Brown, and yet within the commonwealth

you probably won’t find three decent restaurants in a row that serve

lunch and don’t offer it on the menu. Another thing we learned is where

it came from (and why it’s called "Hot Brown" when it really isn’t

brown at all – it’s mostly white and yellow).

First

of all, we know that it really is a regional tradition. Outside of Kentucky

almost no one has ever heard of Hot Brown, and yet within the commonwealth

you probably won’t find three decent restaurants in a row that serve

lunch and don’t offer it on the menu. Another thing we learned is where

it came from (and why it’s called "Hot Brown" when it really isn’t

brown at all – it’s mostly white and yellow).

The

sandwich was created in the Roaring ‘20s by chef Fred Schmidt of the

Brown Hotel in Louisville. He was looking for a late-night meal to serve

to customers after dancing in their very popular ballroom and came up with

an idea for a hot turkey sandwich. Turkey, at that time, was almost exclusively

a Thanksgiving and Christmas meat, so this was quite an unusual offering.

The

sandwich was created in the Roaring ‘20s by chef Fred Schmidt of the

Brown Hotel in Louisville. He was looking for a late-night meal to serve

to customers after dancing in their very popular ballroom and came up with

an idea for a hot turkey sandwich. Turkey, at that time, was almost exclusively

a Thanksgiving and Christmas meat, so this was quite an unusual offering.

As

with all regional favorites, there are almost as many ways to make Hot Brown

as there are restaurants that serve it, ranging from really good to really

awful. We've tried several; none can compare to the

original.

As

with all regional favorites, there are almost as many ways to make Hot Brown

as there are restaurants that serve it, ranging from really good to really

awful. We've tried several; none can compare to the

original. This

isn’t the first Louisville distillery to be called Bernheim, but that

long-gone original wasn’t located here. What was here were two smaller

distilleries that were not in the best of shape. One was the dilapidated

Astor, where Henry Clay bourbon had once been made and the other was the

Belmont, most recent home of the Old Charter and I. W. Harper brands.

This

isn’t the first Louisville distillery to be called Bernheim, but that

long-gone original wasn’t located here. What was here were two smaller

distilleries that were not in the best of shape. One was the dilapidated

Astor, where Henry Clay bourbon had once been made and the other was the

Belmont, most recent home of the Old Charter and I. W. Harper brands.

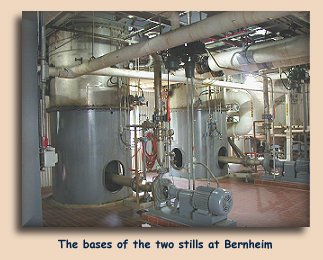

Leaving

the brick warehouses intact, they almost immediately began the task of tearing

down the old distilleries and replacing them with a single, modern facility.

It is equipped with two stainless steel stills (only the heads are copper)

which were originally intended to be used as one for I. W. Harper and the

other for Old Charter. But then they decided to consolidate another of their

recent purchases into the Bernheim plant. The same year Bernheim opened,

United closed the Stitzel-Weller distillery in Shively and moved operations

to the new facility. The brands of Stitzel-Weller (Old Fitzgerald, Old Weller,

and Rebel Yell) were of a type called "wheated" bourbons, where wheat is

used as a flavor grain instead of the more common rye. Bourbon distilled

from a wheat formula requires differences in the way the still is set up

and operated and it made sense to dedicate one of Bernheim’s two stills

to that type and share the other between the two rye-type bourbons.

Leaving

the brick warehouses intact, they almost immediately began the task of tearing

down the old distilleries and replacing them with a single, modern facility.

It is equipped with two stainless steel stills (only the heads are copper)

which were originally intended to be used as one for I. W. Harper and the

other for Old Charter. But then they decided to consolidate another of their

recent purchases into the Bernheim plant. The same year Bernheim opened,

United closed the Stitzel-Weller distillery in Shively and moved operations

to the new facility. The brands of Stitzel-Weller (Old Fitzgerald, Old Weller,

and Rebel Yell) were of a type called "wheated" bourbons, where wheat is

used as a flavor grain instead of the more common rye. Bourbon distilled

from a wheat formula requires differences in the way the still is set up

and operated and it made sense to dedicate one of Bernheim’s two stills

to that type and share the other between the two rye-type bourbons.

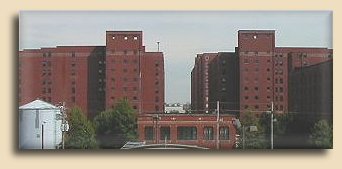

Coincidentally,

in 1996 a devastating fire destroyed the Heaven Hill distillery just outside

of Bardstown, leaving owner Max Shapira in desperate need of replacement.

While rebuilding at Bardstown was certainly an option, the fact that the

future of the practically brand new Bernheim plant was now in doubt opened

the way for some serious (and lengthy) negotiations with Diageo. And in the

spring of 1999 it was announced that Heaven Hill would be the proud new owners

of the Bernheim Distillery in Louisville.

Coincidentally,

in 1996 a devastating fire destroyed the Heaven Hill distillery just outside

of Bardstown, leaving owner Max Shapira in desperate need of replacement.

While rebuilding at Bardstown was certainly an option, the fact that the

future of the practically brand new Bernheim plant was now in doubt opened

the way for some serious (and lengthy) negotiations with Diageo. And in the

spring of 1999 it was announced that Heaven Hill would be the proud new owners

of the Bernheim Distillery in Louisville.

That

was good, because the fancy computerized systems were designed to make whiskey

the way United Distillers thought it ought to be made, but the whiskeymakers

at Heaven Hill felt that wasn't how they wanted it done. So the engineers

and operators immediately had to use their new training to re-write and

re-program the plant to fit their own needs. One result is that Heaven Hill's

familiar brands can be made efficiently without losing the quality people

have come to expect, and another is that a brand such as Ol' Fitz can now

get the kind of attention and craftsmanship it deserves. It's very encouraging

to hear what Jim is saying.

That

was good, because the fancy computerized systems were designed to make whiskey

the way United Distillers thought it ought to be made, but the whiskeymakers

at Heaven Hill felt that wasn't how they wanted it done. So the engineers

and operators immediately had to use their new training to re-write and

re-program the plant to fit their own needs. One result is that Heaven Hill's

familiar brands can be made efficiently without losing the quality people

have come to expect, and another is that a brand such as Ol' Fitz can now

get the kind of attention and craftsmanship it deserves. It's very encouraging

to hear what Jim is saying.

That

is, until Jim cracks open the input hatch of one of these huge tanks and

invites John to have a sniff. John takes a deep snort, expecting the familiar

and delightful fragrance of yeast and whiskey and is quickly knocked

backward by the intensity of it. We all have a good laugh, and you can bet

that when Linda takes a whiff, it's with the proper amount of caution.

That

is, until Jim cracks open the input hatch of one of these huge tanks and

invites John to have a sniff. John takes a deep snort, expecting the familiar

and delightful fragrance of yeast and whiskey and is quickly knocked

backward by the intensity of it. We all have a good laugh, and you can bet

that when Linda takes a whiff, it's with the proper amount of caution.